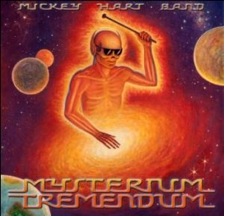

The Mickey Hart Band’s just-released album, Mysterium Tremendum, is a musical marvel and a sonic masterpiece. Over the course of 12 songs stretching to about 74 minutes, the eight-piece band, together in this form less than a year, sounds like old pros who have been playing together for ages.

This is the first Mickey solo album since 1996’s Mystery Box to be based around English-language songs. As with that disc, lyric contributions from Robert Hunter dominate, though this time Mickey himself also penned effective words for several songs—who knew? The MHB boasts two superb singers—the gravel-voiced (but still sonorous) Tim Hockenberry and gospel/soul-influenced Crystal Monee Hall—who bring tremendous character to every song. They trade off on lead vocals, duet on some tunes and also harmonize beautifully throughout. Several songs feature stacked vocals that have a choir-like fullness, and catchy choruses abound—not usually the coin of the realm in Mickey’s projects.

As you’d expect from a Mickey Hart album, however, there are literally hundreds of rhythms pulsing through the album, and not just percussion—though there’s plenty of that, between Mickey’s acoustic/electronic setup, talking drum master Sikiru, traps drummer Ian “Inkx” Herman, and guest appearances by Mickey’s other Global Drum Project mates, Zakir Hussain and Giovanni Hidalgo. MHB lead guitarist Gawain (pronounced “gow-an”) Matthews contributes a fantastic array of rhythms (and leads) with his arsenal of axes, too— long, liquid slide here, funky wah-wah there, chopped chord bursts somewhat reminiscent of U2’s Edge. Widespead Panic bassist Dave Schools brings a dependably deep bottom to the proceedings, as well as lines that occasionally sing, and Hockeberry and Ben Yonas drop various keyboard textures into the mix. (Hockenberry also plays atmospheric trombone on a couple of songs.) Other guests include, on one song each, bassist Reed Mathis (Tea Leaf Green) and guitarist Steve Kimock (who has often played with Mickey over the years).

Also layered into the dense “weave” (as Mickey calls it), are countless electronically triggered samples, encompassing everything from unusual instruments, to bits from Mickey’s enormous collection of “ethno” recordings (such as Mbuti pygmies), to more than two dozen of his much-publicized “sonifications” extracted from the far reaches of the universe. You know Mickey—he’s always got something strange and wonderful up his sleeve (and at his fingertips). In this case, outer space waves and pulses have been captured by radio telescopes, and through a complex process few of us could hope to understand, been converted into sound waves and made “musical.” Everything from solar winds, to the orbits of various planets in our solar system, to different galaxies and cosmic microwaves become part of the dense tapestry of rhythms and melodies on the album.

Add in exotica such as the ominous hum/buzz of an ancient instrument called a bullroarer (which is swung in a circle to create sound), sacred Tibetan skull drums (damaru), atmospheric rainforest sounds and even earthquake rumbles, and you’ve got a strange and richly detailed landscape under conventionally structured songs. This is trance music, dance music, space music, flowing ballads and gritty rock ’n’ roll. There are flavors from Africa and the Middle East and, in a couple of guitar solos, (probably unconscious) nods to Pink Floyd and Quicksilver Messenger Service. It’s a lot to absorb—play it loud (or on headphones)!—but that’s one reason why multiple listens will reveal new elements each time.

Amazingly enough, the band can reproduce the album’s intricate textural mélange onstage, too. As Ben Yonas, who co-produced the album with Mickey and was chief engineer on the project, points out, “The live show is really an extension of the record.” But the album also captures the group’s live skill and energy. In concert, too, the band intersperses a still-growing selection of newly arranged songs by (or associated with) the Grateful Dead into their impressive body of original tunes. Any way you slice, this band is a trip.

In late February, while the album was still being mixed, I had the opportunity to go up to Mickey’s fabulous Studio X, in rural Sonoma County, to talk with Mickey, Ben Yonas and Dave Schools about the band and the making of the album. What follows was pieced together from separate interviews at the studio that day.

SONIFICATIONS

How is it that light impulses get sonified?

Mickey: You put them in a very powerful algorithm and change the form. Anything that has a vibration in the universe—planets, comets, the sun, seed events like the Big Bang— have a light or radiation that can be read on a spectrum. They all travel within their own bandwidth, so what you’re doing in this case is changing light to sound. Then you take the raw sound, which is mostly noise—there are a lot of collisions up there: bumps and thumps and chirps; a lot of things you would probably call noise— and turn it into some place in between perhaps—something that would be recognized as music, where the ear would say, “Hey, we’re close.”

Tone?

Mickey: Not necessarily. Rhythmic impulse. To make it something the ear wants to hear. The music we’re involved in is still basically a rock ’n’ roll kind of format. I like dance bands and I like trance music and I like improvisation. So how do you make the science move in and around that and have fun with it, as opposed to it dominating the music? That was the challenge. Not treating these sounds as an afterthought, but instead treating them like an integral part embedded in the music, and also in the transitions in between songs. It’s a major weave. The challenge was to marry them and have them dance in the two sound worlds.

You’ve never shied away from noise.

Mickey: That’s true. I have a part of me that’s a “noisician”—that’s someone who really likes noise. Jerry and I both really liked noise; it was one of our greatest pleasures. Phil was also into noise, and of course Kreutzmann plays the drums, which is a noise instrument. We were noisy guys. Bob a little less so, I think, though he likes to get it going, too, sometimes. [Laughs]

But this is really serious noise. So we opened it up, brought it down in the spectra, played with it, had some fun with it, sound-designed it. Sculpted it, you could say.

Back 20 years ago, when I was writing my books [Drumming at the Edge of Magic and Planet Drum], the technology wasn’t there to capture the Big Bang—which supposedly happened somewhere between 10 and 20 billion years ago—till [Nobel prize-winning UC Berkeley astrophysicist] George Smoot pinned the tail on the donkey. So when I learned that somebody actually discovered the Big Bang had waveforms, everything just lit up for me: Now I can hear the beginning of time and space, the beginning of creation, the down beat, the moment the groove began!

George was able to read the remnants of the seed sound of the cosmic low end of the universe. That’s a place to start my sonic story.

I presume you know Smoot?

Mickey: Oh, sure. I met him at Kaiser [Convention Center] in Oakland years ago. He was a fan. Not really a Dead Head, but he liked the music. The astrophysicists love this stuff. They don’t tend to think about the sound, so this is new for them, too.

You don’t do the sonfications yourself do you?

Mickey: No, no, no! [Laughs] I have a team doing sonifications. Keith Jackson over at [UC Berkeley’s] Lawrence Berkeley Lab gathers the information from the radio telescopes, and Mark Bellora at Penn State sonifies it. [Perrin Meyer, an advanced software R&D specialist at Meyer Sound in Berkeley, also played an integral role working with the data sets.]

This is real stuff from space. This isn’t like [British composer Gustav] Holst making Venus the most violent planet in the solar system [in his famous orchestral work, “The Planets,” which premiered in 1918]; this is nonfiction. The universe has been fictionalized a lot sonically. I didn’t want to go there.

Didn’t you play some of the sonifications with the Rhythm Devils before you formed this band or started work on this album?

Mickey: That’s right. I’ve actually put about three years into this. I was playing a couple of these songs in the Rhythm Devils and also the sonifications. On one tour we played a different sonification each night—I think it was 23 dates.

You know, Phil was of considerable inspiration at the beginning of this. He knew a lot about the cosmology and the nature of color and a lot of things that I wasn’t that tuned into. He told me about connections between the science and the mythos and the mystic—more than I knew.

So I came back [from touring with The Dead in 2009] and I thought, this could be more than just long tones from space that I was playing on a keyboard. I started making rhythms out of them. How do you deal with this vibratory energy? What meaning can you make of it? What can you do with it? And how can you take it back to the people?

BEGINNINGS OF THE ALBUM

Dave Schools: I guess this album really began with the elements of space sounds, a lifetime of Mickey’s recordings, including his [ethnic] field recordings, and then hours and hours of crazy fun in the studio with people like [Steve] Kimock and myself. It was a bunch of us playing around with sounds and jamming, and at that point not really knowing where it was going to go.

How did you hook up with Mickey originally?

Dave: I moved here around five years ago. Mickey and I shared a manager, Brian Schwartz, who was working with the Rhythm Devils. Mickey and I had played together a few times, but we’d never met as neighbors—I live about five minutes down the road. Anyway, we started to get together for some jam sessions. I have a reputation as a lover of space bass, and he’s right in there with that, of course, so we had a lot of fun. In fact, the first time I came over here to play, I just plugged in and then he took a pedal board with a whole bunch of effects, put them in his lap, and I just played along with these grooves. He was twisting knobs like a mad scientist!

All these jams with me and Kimock and Mickey and his lifetime of recordings got cut up and reworked, and these songs [on the album] evolved from those 20- and 30-minute grooves. That’s what we had before Ben [Yonas] and the others came in.

Ben,how did you come into this scene?

Ben Yonas: Through Howard Cohen [Mickey’s longtime production manager]. I manage a lot of different musicians in different genres. Howard knew some of my hip-hop clients who were doing well at the time, like Zion I and Amp Live and Jazz Mafia, and he knew about my production company and my management company [Yonas Media]. Our model is an independent model, with direct-to-fan marketing. So Howard contacted me and I came up here, and Mickey and I connected pretty much right away.

When I played him my reel of what I’d done, a lot of it was pretty artsy stuff. Mickey, of course, is a legend for traveling the world and recording all over the place, and literally the week before I came up here, I had been in Hungary recording an album for an amazing Gypsy band called Parno Graszt. I had brought all this high-end audio gear to this village in Hungary and we made the record in a barn that had amazing acoustics but also had chickens outside making noise, and takes would get interrupted by people opening doors. No one in the band spoke English. I shared my story with Mickey and he could definitely relate. [Laughs]

That’s his world.

Ben: That’s right. If anybody would know what it’s like to make an acoustic record in a barn in Hungary, it’s Mickey Hart. So we had a lot of similar interests.

Then, I was totally blown away by what I heard that he was working on. I walked in here to 26 musical landscapes, or beds, that Mickey had been developing with a team of other collaborators. Hopefully someday there will be a release of some that early music, which was more focused on drones and space and texture.

When you say there were 26 beds, what is the range of the types of things that were there?

Ben: Well, look at how “Heartbeat of the Sun” evolved. The version on the record has Crystal flying around, singing in between samples of various Mickey Hart Collection recordings. The band is sort of pulsing with it all. It’s an old composition of Mickey’s that we’re reinterpreting. If you take away Crystal and some of those sounds, you will hear what I walked into a year ago. Harmonically it’s about the drone, and as a piano player I wanted to move away from that and expand it. But I’ve also learned to embrace the drone. You don’t need a ton of chord changes to engage people. You need really crazy, cool, intricate rhythmic ideas, and it’s more about energy and intention.

The perspective I brought in was, “OK, let’s go through these beds and see if we can turn them into songs." Mickey was sitting on a vast pile of Hunter lyrics, so I was encouraging Mickey to go and pair them with some of these musical ideas, and then we just started writing. I love to build a team around a project, so I just called some of the best songwriters I know, like Cliff Goldmacher and Andre Pessis. My own strengths are more as a piano player and producer and arranger. I’m not really one to pair lyrics with song and melodies. So it was really Mickey and Andre and Cliff who got the ball rolling shaping the songs.

But this isn’t a conventional song world. We weren’t restricted to four minutes and we weren’t trying to write a “hit,” so the chorus didn’t have to happen 30 seconds into the song. From the beginning, we wanted the songs to have the space to breathe.

Although these songs also have strong hooks.

Ben: It’s all about finding a balance. We wanted to create music that lasts and that people can sing along to. When people sing along on the chorus the first time through the song in a new town, that feels really great.

I know your management company handles the two singers, Crystal and Tim, and you knew [guitarist] Gawain Matthews. Is it fair to say you essentially put the band together?

Ben: Mickey and I have done everything together. There’s no clear-cut answer to who brought who in. Did I have a lot to do with it? Yes. Crystal and Tim were two singers I had worked with. They knew of each other but hadn’t worked together before. Each of them on their own is good enough to be a lead singer—these are not backup singers, though they’re great at that as well. Tim came off playing with Trans-Siberian Orchestra in small arenas, and Crystal had been Joanne in Rent along with a lot of other stuff.

I first met Crystal when she was a backup singer on an album I was working on by Moby’s lead singer, Shayna Steele, who’s incredible. There was a choir with six vocalists and—no disrespect to the other five, who are all exceptional—when we were going through the mikes to hear each of their voices, when I got to Crystal I remember looking back at Shayna and saying “Who is that?” She had ridiculous tone. I immediately wanted to work with her. So now we’ve worked together for years.

As for Gawain, I used to live with him. I convinced him to move to the Bay Area. He’s from Wales originally, but he grew up in Utah. I was totally blown away by his playing when I met him years ago. He can really play anything and he never plays it the same way twice. He’s got huge ears. Does he sound like Jerry Garcia? No. He’s not trying to sound like Jerry Garcia. He’s just trying to do what he does. If I’m making a record, Gawain is the first guy I call if I want layers and textures. He’s one of the best studio players I know. He’s a sound designer, the same way Mickey is a sound designer. Gawain takes it really seriously. He’s turning knobs and dialing up space and all these sounds—his pedal board is the most complicated thing I’ve ever seen.

We didn’t audition lots of people. We just started collaborating. It wasn’t, “Here are 12 songs, learn these.” It was, “Here are some songs that are sketched-out; do your thing with them,” and it was also, “Here are some songs that aren’t even finished.” Crystal and Tim both wrote big chunks of this record. A lot of the melodies are their melodies. That’s one of the areas where we all connected in the creative process.

Mickey: When they first came in, we offered them different sonifications and I wanted to see how they would react to them; let them have some kind of relationship with the cosmic sounds. See if they could find a way to make sense of these powerful sounds from the cosmos. And they jumped right in.

Ben: This isn’t a bunch of hired guns; it’s a band. We finished rehearsal here yesterday at 5, and at 8:30 everyone was still here listening to the record and hanging out. I’ve never been part of group with such good chemistry. Our tour bus is fun to be on. It’s such an eclectic group of folks, so many different personalities. You’ve got a Grammy-winning Nigerian badass drummer, Sikiru, who’s this super sweet, funny guy. And then you’ve got Schools—Bass Mountain—who holds us all together; he’s beautiful. He was already collaborating with Mickey.

The first lineup I saw had another percussionist, Greg Ellis, and a different bass player, Vir McCoy, though before that, Dave and Vir both played at Wavy’s Birthday Party with the foundation of what the group would become.

Ben: That’s right. We had already been working with Dave, but he was on the road with Widespread Panic [when the first Mickey Hart Band shows took place]. And Dave was here before me, as was Inkx, who had been recording and collaborating with Mickey for a while before I walked through the door. He’s a perfect fit; an amazing drummer.

Sikiru, Inkx, Dave and Mickey had already been working together, and I came in and said, “Let’s check out these singers, and my buddy plays the hell out of the guitar—I don’t know if any of you know who he is, but just listen to him.”

Dave: I’d work on it, go off on a Panic tour and come back in and I’d have a totally different perspective on how something had evolved over three months. In the beginning it was me and Kimock and Mickey’s archival recordings, and the next time I came back there was a six-piece band, and then the next time it was an eight-piece band with two vocalists who are astounding.

Ben: From the beginning, our approach was an organic one: Let’s create a project, let’s create something that we can go out and tour and write some great songs for and shape the material together. But everything was created out of the world that Mickey built. He started the whole process, because he’s out here making music every day. He’s the hardest-working guy I’ve ever met. Fourteen hours into a day he’ll say, “OK, let’s get going; let’s work!” [Laughs] And I work hard, too, so we go to bed at 4 in the morning.

How important was it that some of Hunter’s lyrics tie into the cosmic sounds that started as the basis of the album?

Mickey: It was very important. Normally when I interact with Bob—or “Robert” if you prefer—I usually just give him the grooves and he comes up with the words. I don’t like to try to influence what he writes, because every time I try, he comes up with a better idea anyway, so I just gave up! [Laughs] In this case, though, the theme was about man and the universe, so I was looking for things that might tie into that.

Well, that’s pretty broad!

Mickey: Yeah! Well, and also these cosmic events and what our relation is to all these events. What he told me is, he stepped away for a couple of weeks and really got inside the project and the music, and let it wash over him. Then he delivered the motherlode!

It’s just like with all those Garcia-Hunter songs for the Grateful Dead—they define a certain cosmology, though you can’t really put your finger on what it is exactly. That’s what he’s doing with these songs, too.

Although they’re certainly not all about space, by any means. And you’ve written some lyrics, too.

Mickey: I assure you, I’m not trying to compete with Robert Hunter! [Laughs] But I did write a few things.

Ben: Mickey’s a good writer. Just reading the lyrics, you might not even know immediately whose lyrics are whose. He wrote “Endless Skies” for his wife [Caryl], and a couple of others songs, too [including “Djinn Djinn” and “Time Never Ends”].

RECORDING

Mickey told me that the main sessions for the album went incredibly quickly, which surprised me, given his reputation for spending weeks and months and years in the studio.

Ben: It’s true. Eighty percent of this record was done in three days, which is how I usually make records. You focus on pre-production and on developing great material. You rehearse it and tour it, and then the studio is here to pull out and capture that energy. We try to create a vibe that’s similar to what happens onstage when we’re all smiling and looking at each other and not thinking about recording, but instead just playing and interacting.

That guitar solo on “Cut the Deck” is the live guitar solo, that’s the live bass, the live drums. It’s not something we edited together and tried to create. You can never do that—you can’t go in and create performances that truly interact. You can make electronic records that are little loops of things, but if you want to create that energy of people acknowledging their parts and flowing together, it has to be real and it has to flow naturally. So at the height of the guitar solo, Inkx went to the crash cymbal and Dave went low on the bass because that’s what they were feeling at that moment in the room. That’s how I’m wired. I’ve also made jazz records my whole life, so that’s where I come from.

If so much of the record was done in three days, what has the last six months of work on the album been about?

Ben: The last six months has been shaping it. This was not like other records I’ve ever made, where we arrange the song and decide the guitar solo is 16 bars because its going to be a four-minute song. “Endless Skies” was recorded live in the studio as a 17 ½-minute song. Most of these songs came in at 10 to 12 minutes. One of the debates we had was, “Is an 80-minute album OK?” We just said: “We want these songs to breathe.”

We’re not making this to be played on the radio by some triple-A [format] radio guy. If they want to do that, they can cut out the intro and the outro and take the four minutes in the middle! There will be radio edits. But it’s not about that. It’s not about creating music for the industry. It’s about Mickey’s intention as an artist and going with that and trying to channel his approach.

I’ve learned so much from Mickey about sitting on a groove and getting into a zone and into a space and embracing it, and then doing what Mickey does better than anyone I’ve ever met, which is playing into the processing [echoes, reverbs, chorusing effects, etc.]. When you listen to his records, so much of it is sound design—using sounds in interesting ways and using lots of uncommon sounds and processing.

What Mickey’s almost invented with his Beam and the world he’s built in RAMU [his sophisticated setup of electronics and sampled sounds and instruments] is that the process shapes how you play. If you’ve got a crazy effect on something, people are going to perform differently with that than if you perform [sounds] clean and then go in later and add processing in post-production. So the musicians are playing to the effects we’re adding, and everything is in real time.

All of us have learned about Mickey’s world and gone after it. The singers did not have harmonizing delay effects machines before Mickey Hart. If you listen to the sound of this band, almost everything is processed. I guess Gawain was pretty processed already, but most were not wired with that approach. Most singers don’t think, “With this button I can sound like a Tibetan monk chanting, and over here I’ve got a seven-part harmony that’s been stacked and arranged for the chord of the song, so now I can be a choir.”

Dave: Mickey has dragged me kicking and screaming out of a 10-year cycle of refining my bass playing mostly down to fingers and amplification. I used to really be into processing and weird effects, but I started moving out of that around the time [late Widespread Panic guitarist Michael] Houser got sick; I don’t know why. I started using flat-wound strings and playing four-string basses for all my other projects, and going for a real traditional Led Zeppelin II kind of big, boofy bass sound, and that’s where I was when I came into this. And then Mickey shows up with a pedal board and he’s saying, “Get that six-string out!” and I’m showing up with these antiquated [four-string] jazz basses. “Where’s the Modulus [bass]? Let’s send you down to Meyer!” [Laughs] It’s been cool. I like it. Here I go, off on another turn.

Jonah Sharp has been an integral part of Mickey’s electronics and sound design work the past few years. Did he help on the album?

Ben: Yes, Jonah was a big part of this record. He’s a great sound designer who’s done so much amazing work with Mickey through the years. I walked into a pretty awesome situation here, so I don’t take the credit. Jonah’s very much been part of the process. We have very different roles. Yes, I’m doing processing and some electronic stuff, but Jonah needs to be credited with a lot of that work. There are also other sound designers who have worked on this project, like Charles Stella, who’s a producer and electronic musician I’ve worked with for years.

THE ALBUM TITLE

I think I first encountered that phrase—“mysterium tremendum”—reading Mircea Eliade in college, The Sacred and the Profane.

Mickey: Right, Eliade. Though [German theologian] Rudolph Otto used it before him. It means a few things. It’s the trembling you experience when you come into contact with the great mysteries, or the divine; whatever you want to call it. I thought it fit in with what we’re doing because what is this thing? Is it the song of the universe? Dancing with the cosmos? It has a resonance with the mysterium.

It’s all part of [mythologist] Joseph Campbell territory.

Mickey: I was thinking the other day about Campbell in relation to this. Joe would sometimes get so into telling these stories that he would actually tremble, like he was experiencing an epiphany in the retelling of these myths. It was almost like he was becoming part of it, and his belief system would kick in, and you could see him start to tremble.

PLAYING DEAD

Ben: From the beginning we knew that this band needed to focus on a new body of work and create an album. That’s where we had put all our energy, but now we’re embracing more of the Grateful Dead songbook. Yesterday we worked on “Morning Dew” and “Stella Blue.” Crystal does such an amazing job on these and “Brokedown Palace,” which we’ve been doing for a while. People freak out when they hear that—this church girl from Virginia singing her heart out.

We’re not out there trying to compete with the Dark Star Orchestras of the world, and we haven’t gone in and studied how Jerry played the guitar on this or that song. We’re trying to reinvent them with the musicians we have, enjoying them—a lot of these are new for most of us—and embracing them.

They’re great songs.

Ben: They’re amazing songs, and we want to do some different things with them. So, for example, we spent yesterday re-creating the groove of “Samson and Delilah.” We’re breaking rules, and some fans might say, “Hey, that’s not how you play it—you’re missing this part.” In most of them we’ll give you what you’re used to in some part of the song, and in some, a lot of what you’re used to. But we want to approach each one individually and see what comes out of us.

Dave: I’ve been helping coach people on the Dead stuff, but it’s more of a philosophical thing I’m trying to get across. I tell Gawain: It’s not how you play the lick, it’s how you approach the playing of the lick and the theme and the variation. You have to become—I’m going to make up a word here—a “meloditician”—like a mathematician, except with melody. It’s like turning on a spigot. The vocabulary has to flow like the way we converse, and it has to be done musically. It’s a poetic way of conversing and passing ideas around. I think I understand the philosophy behind this music, so when we do play Grateful Dead songs, we can approach them with the right intent, as opposed to copying it.

You know, I can play Grateful Dead music until the cows come home, but I can’t play it like Phil—no one can. I like to say he’s an “un-bassist.” I’m a bassist. Most bass players don’t think like Phil. If you’re copying his licks, you’ve missed the point already. It’s about letting music play you and through you.

Mickey: I like playing Grateful Dead music, and I really like playing it with this group because we play it a little different. The dragon can come out with this band. They all listen really well, so they get my nuances and we lock in together.

I don’t want Gawain to imitate Jerry, but there are certain things Jerry came up with that make that song that song. Even though “Fire on the Mountain” is jammy, it has certain themes that make it “Fire on the Mountain,” so you can play with that and around it. Gawain does a good job and pays proper respect, but he’s not a Jerry clone. So what we’re giving people is a different context for these Dead songs. And we’re picking songs that play to the strengths of this band.

And we’re open to doing other stuff, too. The other day we played “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” and we just killed it. This band is flexible and young and they like to play long. They have the energy for it. I just had to train them and let them know it was OK, so when we’d be going for 20 or 30 minutes on a tune and they’d want to end, I’d say, “No, no, no! You’ve got to find the song, and then it becomes a part of you and you a part of it.” That’s the name of the game with this kind of music. Fortunately, they’re young and corruptible. [Laughs]

(For more info and to order the album, go to mickeyhart.net.)